Tattoos have existed on the skin for thousands of years, with countries and cultures all over the world having different methods and styles of tattooing. But perhaps none have ingrained themselves into a culture more than in Polynesia.

From tribes and tatau to The Rock, we’re going to be taking a look at the history of Polynesian tattoos.

Although European explorers first visited Polynesia in 1595, it wasn’t until Captain James Cook navigated the islands in 1769 that records of these tribal tattoos were documented.

Joseph Banks, a naturalist onboard James Cook’s ship, HMS Endeavour, is credited with the first written reference to the word “tattoo”. In his journal, Banks wrote, “I shall now mention the way they mark themselves indelibly, each of them is so marked by their humour or disposition”.

After visiting Tahiti and witnessing tattooing for the first time, Captain Cook spoke of “tattow”, which is taken from the Samoan word “tatau” and, similarly, the Marquesan term “tatu”.

It was on his return to Europe in 1771 that the word “tattoo” entered local dialect. It became rapidly famous due to the tattoos of Ma’i (known as Omai in Britain), a Tahitian brought along by Cook and the first ever to travel to Europe.

Although Europeans at this time were now aware of this particular style of tattoo, they did not yet know of the many variations of Polynesian tattoos that could be found on the islands.

Over in New Zealand, the largest country in Polynesia, the indigenous Māori people practised a form of tattooing known as tā moko.

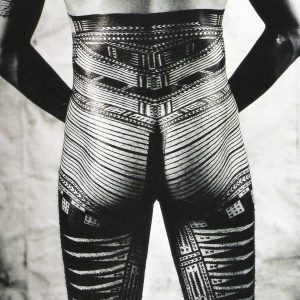

Tā moko is distinct from tattooing as the skin is carved by chisels known as “uhi”, rather than punctured by needles. Usually these Māori tattoos are found on the faces of those who received them, although they could also be seen on the buttocks and thighs.

Māori tattoo artists were known as tohunga-tā-moko, or “moko specialists”. Traditionally, tohunga-tā-moko were considered “tapu”, meaning sacred. (James Cook would derive the English word “taboo” from “tapu” after his visit to Tonga in 1777.)

In pre-European Māori culture, the majority of high-ranking people received “moko”, while those who went without were seen as being of a lower social status.

Since the ‘90s, there has been a resurgence in the practice of tā moko for both men and women and is seen as a sign of cultural identity and of the revival of the culture itself.

Unlike its origins, most tā moko today is applied with a tattoo machine, although there have been many artists bringing back the use of chisels.

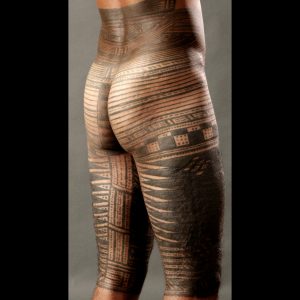

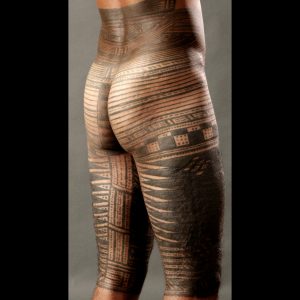

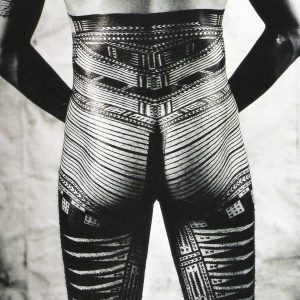

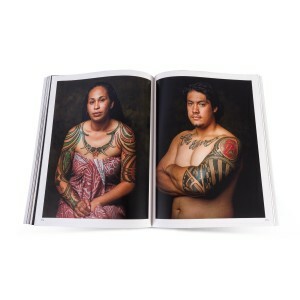

Over in the Polynesian island of Samoa, “tatau” is split into two forms, “pe’a” for males and “malu” for females.

The traditional male tattoo of the pe’a covers the body from the waist to just past the knees, and is undertaken by “tufuga ta tatau”, aka “master tattooists”.

The process of tattooing the pe’a is extremely painful. The tufuga ta tatau traditionally used a set of handmade tools made from pieces of bone, turtle shell and wood to create the body tattoos.

Tattooing a pe’a could take many weeks or even months to complete and it was not uncommon for a small group of boys to be tattooed at the same time.

For females, the malu covers the legs from just below the knees to the upper thighs. Typically, the designs are finer and more delicate compared to the pe’a.

Originally, only the chief’s daughter was eligible to wear the malu and it was tattooed in the years following puberty. Women with the malu were expected to represent their families at ceremonies.

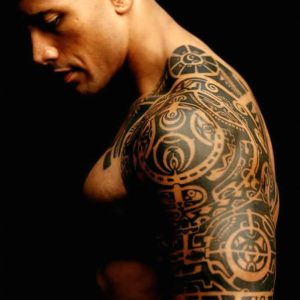

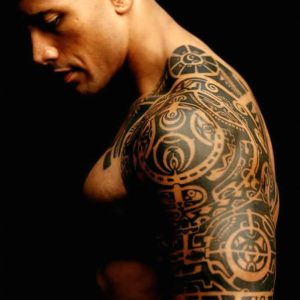

In recent times, one of the most popular examples of Samoan tattoos can be seen on Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson, who has a partial Samoan pe’a tattooed on his left side.

As with all Samoan tattoos, The Rock’s pe’a is comprised of various symbols, each representing something that is important to him and he’s passionate about, culminating in a story about his life, journey and ancestors.

Some of the symbols that can be seen on his pe’a include coconut leaves (denoting a Samoan chief-warrior), isa/ga fa’atasi (“three people in one” – representing Dwayne, his wife and daughter) and two eyes (symbolising his ancestors watching over his path).

Celebrities like Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson have certainly helped Polynesian tattoos come into the limelight, with the traditional tattoos now even extending to the likes of Disney films.

Disney’s 2016 animated movie ‘Moana’, which also featured The Rock, gave a new generation a brief look into Polynesian culture, including how such tattoos can tell a personal story.

Although Polynesian tattoos were traditionally done by natives in their respective islands, the popularity of tattooing today has meant that many artists around the globe have turned their hand to these tribal tattoos.

Aside from Polynesian artists, artists like

Brent McCown (Australia),

Manos “Manu” Paterakis (Greece) and

Chris Higgins (UK) are keeping the spirit of tatau alive and bringing it to customers worldwide.

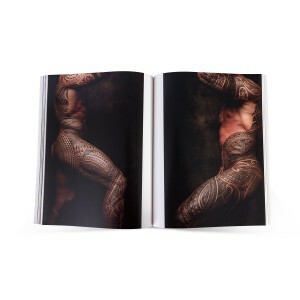

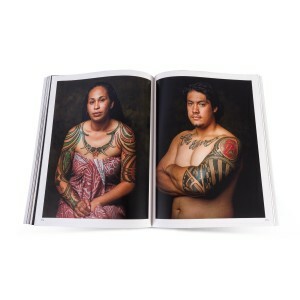

Over in the United States, an exhibition entitled ‘

Tatau: Marks of Polynesia’ further addressed the key role that tattoos play in the preservation and propagation of Samoan culture.

Curated by master tattoo artist Takahiro “Ryudaibori” Kitamura at the Japanese American National Museum, Tatau: Marks of Polynesia explored the history of tatau and how it has continued to thrive in the modern world.

With the exhibit now finished, you can discover the beauty of Polynesian tattoos yourself with the accompanying book of the same name.

The

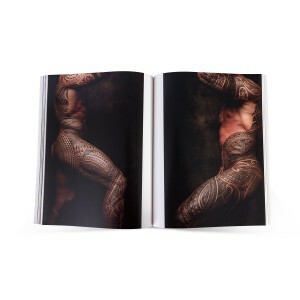

Tatau: Marks of Polynesia book features 286 pages of full colour photos from the works of artists like Su‘a Sulu‘ape Alaiva‘a Petelo, Su‘a Sulu‘ape Peter, Su‘a Sulu‘ape Paul Jr., Su‘a Sulu‘ape Aisea Toetu‘u, Sulu‘ape Steve Looney, Tuigamala Andy Tauafiafi, Mike Fatutoa, and Sulu‘ape Si‘i Liufau.

“Your necklace may break, the fau tree may burst, but my tattooing is indestructible. It is an everlasting gem that you will take into your grave.” – Verse from a traditional Polynesian tattoo artist’s song.

Although Europeans at this time were now aware of this particular style of tattoo, they did not yet know of the many variations of Polynesian tattoos that could be found on the islands.

Over in New Zealand, the largest country in Polynesia, the indigenous Māori people practised a form of tattooing known as tā moko.

Tā moko is distinct from tattooing as the skin is carved by chisels known as “uhi”, rather than punctured by needles. Usually these Māori tattoos are found on the faces of those who received them, although they could also be seen on the buttocks and thighs.

Māori tattoo artists were known as tohunga-tā-moko, or “moko specialists”. Traditionally, tohunga-tā-moko were considered “tapu”, meaning sacred. (James Cook would derive the English word “taboo” from “tapu” after his visit to Tonga in 1777.)

In pre-European Māori culture, the majority of high-ranking people received “moko”, while those who went without were seen as being of a lower social status.

Since the ‘90s, there has been a resurgence in the practice of tā moko for both men and women and is seen as a sign of cultural identity and of the revival of the culture itself.

Unlike its origins, most tā moko today is applied with a tattoo machine, although there have been many artists bringing back the use of chisels.

Although Europeans at this time were now aware of this particular style of tattoo, they did not yet know of the many variations of Polynesian tattoos that could be found on the islands.

Over in New Zealand, the largest country in Polynesia, the indigenous Māori people practised a form of tattooing known as tā moko.

Tā moko is distinct from tattooing as the skin is carved by chisels known as “uhi”, rather than punctured by needles. Usually these Māori tattoos are found on the faces of those who received them, although they could also be seen on the buttocks and thighs.

Māori tattoo artists were known as tohunga-tā-moko, or “moko specialists”. Traditionally, tohunga-tā-moko were considered “tapu”, meaning sacred. (James Cook would derive the English word “taboo” from “tapu” after his visit to Tonga in 1777.)

In pre-European Māori culture, the majority of high-ranking people received “moko”, while those who went without were seen as being of a lower social status.

Since the ‘90s, there has been a resurgence in the practice of tā moko for both men and women and is seen as a sign of cultural identity and of the revival of the culture itself.

Unlike its origins, most tā moko today is applied with a tattoo machine, although there have been many artists bringing back the use of chisels.

Over in the Polynesian island of Samoa, “tatau” is split into two forms, “pe’a” for males and “malu” for females.

The traditional male tattoo of the pe’a covers the body from the waist to just past the knees, and is undertaken by “tufuga ta tatau”, aka “master tattooists”.

The process of tattooing the pe’a is extremely painful. The tufuga ta tatau traditionally used a set of handmade tools made from pieces of bone, turtle shell and wood to create the body tattoos.

Tattooing a pe’a could take many weeks or even months to complete and it was not uncommon for a small group of boys to be tattooed at the same time.

For females, the malu covers the legs from just below the knees to the upper thighs. Typically, the designs are finer and more delicate compared to the pe’a.

Originally, only the chief’s daughter was eligible to wear the malu and it was tattooed in the years following puberty. Women with the malu were expected to represent their families at ceremonies.

Over in the Polynesian island of Samoa, “tatau” is split into two forms, “pe’a” for males and “malu” for females.

The traditional male tattoo of the pe’a covers the body from the waist to just past the knees, and is undertaken by “tufuga ta tatau”, aka “master tattooists”.

The process of tattooing the pe’a is extremely painful. The tufuga ta tatau traditionally used a set of handmade tools made from pieces of bone, turtle shell and wood to create the body tattoos.

Tattooing a pe’a could take many weeks or even months to complete and it was not uncommon for a small group of boys to be tattooed at the same time.

For females, the malu covers the legs from just below the knees to the upper thighs. Typically, the designs are finer and more delicate compared to the pe’a.

Originally, only the chief’s daughter was eligible to wear the malu and it was tattooed in the years following puberty. Women with the malu were expected to represent their families at ceremonies.

In recent times, one of the most popular examples of Samoan tattoos can be seen on Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson, who has a partial Samoan pe’a tattooed on his left side.

As with all Samoan tattoos, The Rock’s pe’a is comprised of various symbols, each representing something that is important to him and he’s passionate about, culminating in a story about his life, journey and ancestors.

Some of the symbols that can be seen on his pe’a include coconut leaves (denoting a Samoan chief-warrior), isa/ga fa’atasi (“three people in one” – representing Dwayne, his wife and daughter) and two eyes (symbolising his ancestors watching over his path).

Celebrities like Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson have certainly helped Polynesian tattoos come into the limelight, with the traditional tattoos now even extending to the likes of Disney films.

Disney’s 2016 animated movie ‘Moana’, which also featured The Rock, gave a new generation a brief look into Polynesian culture, including how such tattoos can tell a personal story.

In recent times, one of the most popular examples of Samoan tattoos can be seen on Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson, who has a partial Samoan pe’a tattooed on his left side.

As with all Samoan tattoos, The Rock’s pe’a is comprised of various symbols, each representing something that is important to him and he’s passionate about, culminating in a story about his life, journey and ancestors.

Some of the symbols that can be seen on his pe’a include coconut leaves (denoting a Samoan chief-warrior), isa/ga fa’atasi (“three people in one” – representing Dwayne, his wife and daughter) and two eyes (symbolising his ancestors watching over his path).

Celebrities like Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson have certainly helped Polynesian tattoos come into the limelight, with the traditional tattoos now even extending to the likes of Disney films.

Disney’s 2016 animated movie ‘Moana’, which also featured The Rock, gave a new generation a brief look into Polynesian culture, including how such tattoos can tell a personal story.

Although Polynesian tattoos were traditionally done by natives in their respective islands, the popularity of tattooing today has meant that many artists around the globe have turned their hand to these tribal tattoos.

Aside from Polynesian artists, artists like Brent McCown (Australia), Manos “Manu” Paterakis (Greece) and Chris Higgins (UK) are keeping the spirit of tatau alive and bringing it to customers worldwide.

Over in the United States, an exhibition entitled ‘Tatau: Marks of Polynesia’ further addressed the key role that tattoos play in the preservation and propagation of Samoan culture.

Although Polynesian tattoos were traditionally done by natives in their respective islands, the popularity of tattooing today has meant that many artists around the globe have turned their hand to these tribal tattoos.

Aside from Polynesian artists, artists like Brent McCown (Australia), Manos “Manu” Paterakis (Greece) and Chris Higgins (UK) are keeping the spirit of tatau alive and bringing it to customers worldwide.

Over in the United States, an exhibition entitled ‘Tatau: Marks of Polynesia’ further addressed the key role that tattoos play in the preservation and propagation of Samoan culture.

Curated by master tattoo artist Takahiro “Ryudaibori” Kitamura at the Japanese American National Museum, Tatau: Marks of Polynesia explored the history of tatau and how it has continued to thrive in the modern world.

With the exhibit now finished, you can discover the beauty of Polynesian tattoos yourself with the accompanying book of the same name.

The Tatau: Marks of Polynesia book features 286 pages of full colour photos from the works of artists like Su‘a Sulu‘ape Alaiva‘a Petelo, Su‘a Sulu‘ape Peter, Su‘a Sulu‘ape Paul Jr., Su‘a Sulu‘ape Aisea Toetu‘u, Sulu‘ape Steve Looney, Tuigamala Andy Tauafiafi, Mike Fatutoa, and Sulu‘ape Si‘i Liufau.

“Your necklace may break, the fau tree may burst, but my tattooing is indestructible. It is an everlasting gem that you will take into your grave.” – Verse from a traditional Polynesian tattoo artist’s song.

Curated by master tattoo artist Takahiro “Ryudaibori” Kitamura at the Japanese American National Museum, Tatau: Marks of Polynesia explored the history of tatau and how it has continued to thrive in the modern world.

With the exhibit now finished, you can discover the beauty of Polynesian tattoos yourself with the accompanying book of the same name.

The Tatau: Marks of Polynesia book features 286 pages of full colour photos from the works of artists like Su‘a Sulu‘ape Alaiva‘a Petelo, Su‘a Sulu‘ape Peter, Su‘a Sulu‘ape Paul Jr., Su‘a Sulu‘ape Aisea Toetu‘u, Sulu‘ape Steve Looney, Tuigamala Andy Tauafiafi, Mike Fatutoa, and Sulu‘ape Si‘i Liufau.

“Your necklace may break, the fau tree may burst, but my tattooing is indestructible. It is an everlasting gem that you will take into your grave.” – Verse from a traditional Polynesian tattoo artist’s song.